Contact: +91 99725 24322 |

Menu

Menu

Quick summary: Grasslands and savannahs are a home for a quarter of the world’s population and habitat for thousands of plants and animals. However, these grasslands are being threatened by land use change and loss of biodiversity The protection and management of grasslands combined with restoration can help to conserve nature and sustain a thriving food system and support livelihoods of local and indigenous communities.

Do you know that grasslands form a major part of the global ecosystem that covers 37% of the earth’s terrestrial area and represent some of the world’s richest and most diverse ecosystems.?

Grasslands and savannahs are a home for a quarter of the world’s population and habitat for thousands of plants and animals. They contribute significantly to food security through providing the proteins required by ruminants used for meat and dairy.

However these grasslands are being threatened by land use change, loss of biodiversity and invasive species and with challenges to manage the endangered species. Their conservation and protection have been virtually ignored and it is necessary that these grassland systems are revived through their sustainable management. Let us look into what are these grasslands, why are they beneficial and how we can conserve them.

The Savannahs, Pampas, Prairies, Steppes, Shrublands are commonly heard grass dominated landscapes indicating the diversity of grasslands. They have appeared millions of years ago due to climate shifts and have been shaped by wildfire and migration of animals. These landscapes play a critical role in building a healthy planet.

Grasslands cover around 40% of planet’s total land, representing 80% of world’s agricultural and livestock area. Most of them are used as rangeland, providing feed for livestock used in meat and dairy production. The extensive livestock grazing provides livelihoods for millions of rural and indigenous people.

There are two main types of grasslands, the tropical and temperate. While the temperate grasslands include the prairies and steppes, the tropical grasslands include the hot savannahs. Rainfall varies from season to season and the temperatures can freeze. The height of vegetation depends on the rainfall. The combination of underground biomass and the rains can wash away nutrients making grassland soils more fertile and conducive to agriculture.

Grasslands support a variety of species. They are home to world’s best known wildlife including savannah elephants, rhinos and lions on the East African side and Bengal tigers, one-horned rhinos and Asian elephants on the low grasslands of Asia.

Grasslands have a great potential to play a role in climate change mitigation related to carbon storage, sequestration and biodiversity preservation. Grasslands can act as a significant carbon sink with the implementation of improved management.

According to FAO, the global carbon stock in grasslands is about 343GT Co2 which is about 50% more than the amount stored in world forests.

What makes grasslands special are that they survive and keep regrowing no matter how much they are munched. They attract wildlife. But these grasslands are today being rapidly converted into farmlands and this where they require help.

The biggest threat to grasslands is their conversion to farmlands to grow monoculture crops like wheat and corn, let livestock graze, growing soya to feed farm animals. This affects the biodiversity with problems of over grazing and over pollution. Grasslands are facing the fastest and highest rates of conversion and degradation of biomes resulting in biodiversity loss, carbon emissions and negative impacts on freshwater systems.

This tends to erode the local and traditional cultures, with unsustainable agriculture being the primary driver. The pressure on these natural ecosystems is often overlooked, despite their relevance with regards to food production, water security, biodiversity, climate mitigation and livelihoods.

The fertile soils provided by these natural grasslands have led to unchecked conversion to croplands and the vast herds of wildlife have been replaced with domestic livestock. With the demand to feed the growing population, these landscapes are undergoing transformation with intensification of agriculture practices.

North America’s Great Plains and Brazil’s Cerrado have lost already about half of their native vegetation.

Less than 10% of these grasslands are protected and the climate changes has caused global warming in Steppes. This degradation amounts to reduction in their ability to store carbon, soil fertility, water table and a healthy habitat for wildlife and people.

Most of the world’s grasslands are on poor quality land with only one-sixth on land that was of high or medium quality. They are showing signs of degradation caused by a number of reasons related to overgrazing, soil erosion and weed encroachment. Population growth, urbanization, land distribution has stopped the traditional grazing systems and are being replaced with continuous overgrazing and subsequent deterioration. The shift towards more processed and prepared foods with higher proportion of animal protein, the strong growth of meat and dairy products and the increase in food demand has led to land degradation due to overgrazing.

The soil organic carbon sequestration potential of the world’s grasslands is 0.01 to 0.3 Gt C/ year.

The grazing management and pasture improvement has a potential for mitigation of almost 1.5 GT CO2e in 2030, with additional reduction possible from restoration of these grasslands. The protection and management of grasslands combined with restoration can help to conserve nature and sustain a thriving food system and support livelihoods of local and indigenous communities.

These approaches could be towards

Some of the practices that can be followed are:

Practices like fertilization and irrigation can improve carbon storage in pastures and improve productivity. There may be a need to offset some of the nitrous oxide emissions from fertilizers and emissions from energy usage in irrigation.

The improved pasture condition, higher forage yields and animal production can be achieved by combining animal, plant, soil and other environmental components. The sustainable grazing management includes a proper stocking rate, livestock type and recovery tome for grass regrowth. Factors like farm topography, weather variation herbage cover, stocking rate, seasonal grazing affects the quantity and quality of pastures.

Practices like reduced tillage, improved fertilizer management, crop rotation and cover crops can potentially sequester large amounts of carbon. It helps to improve the soil organic matter.

The grassland can be divided into paddocks and rotate the grazing animals between them. This helps to recover the grass, prevent overgrazing and ensure better utilization of pasture.

The accumulated thatch and woody growth is removed which helps to reduce the risk of wildfires and promote seed germination. This has to be done in a controlled environment.

Managing weeds and pests in a sustainable way reduces the need for chemical fertilizers which can have an impact on the ecosystem.

Regular monitoring of grasslands helps to identify hot spots and take timely interventions.

Management of sustainable grasslands requires a holistic approach that is dependent on other ecosystem components. The long-term productivity and health of grasslands needs to be kept in mind.

Well managed grazing systems can provide healthy soil and clean water and air for people and wildlife. It can be a part of profitable farming with low costs, improving herd health and reducing labour.

Do you know there is a growing demand for carbon credits from grasslands?

Adopting multi-paddock grazing that involves high density stocking rates, short grazing periods and long rests on small parcels of land improves soil health and builds soil carbon. Building a marketplace that incentivizes farmers and encouraging them to adopt regenerative grazing practices can have far reaching benefits. Nature based solutions have a better advantage compared to technology solutions in generating carbon credits. The soil carbon credits from grasslands are robust. Depending on the climate and soil types, the soil carbon storage can range between 0.5 to 4 MT of CO2 per acre per year.

It is estimated that the current value paid to project developers for these credits would be at least $20 a tonne, an amount that could increase as the carbon markets continue to develop. The opportunity for earning revenues from grassland carbon credits presents a huge potential for changes in land use. There is a lot going on below the surface in grasslands. Grasses, unlike trees keep their collective biomass underground in extensive root systems. Grasslands lock most of the CO2 they absorb away in underground root systems than the visible trunk.

The grassland-based carbon credits almost follow the forestry credits in the voluntary carbon market

The grassland offsets are first focused on protection and preservation. The primary threat to grasslands is agriculture, as tilling disturbs root systems that store soil carbon. The conversion of grasslands to tilled fields is hence avoided. Projects take established grasslands and award credits to owners who keep them in their current state without any conversion. Credits are also awarded for no-till practices that preserve underground biomass.

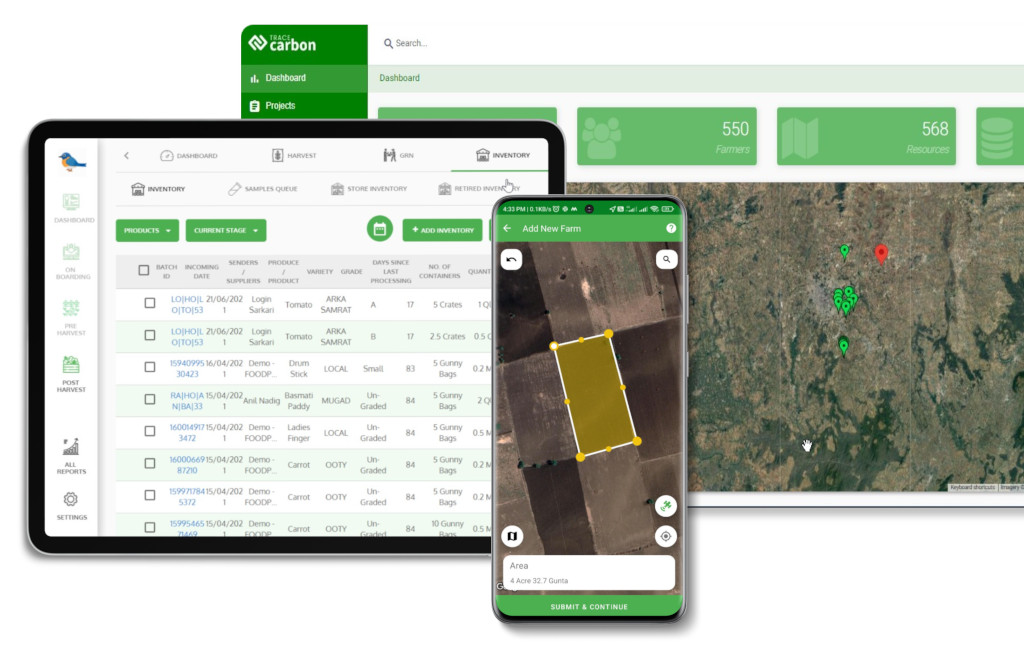

However, these practices have to be monitored accurately and validated with more of transparency and accountability. TraceX is building a DMRV platform for nature based solutions, bridging the trust deficit with quality carbon credits.

The key drivers behind grassland offsets are the ranching and farming communities and the government agencies that support them. The grassland conversion provides a real-world carbon sink, and the time scale is faster compared to growing forests. Grassland sequestration projects form a part of a growing world of nature based offsets for a greener future.